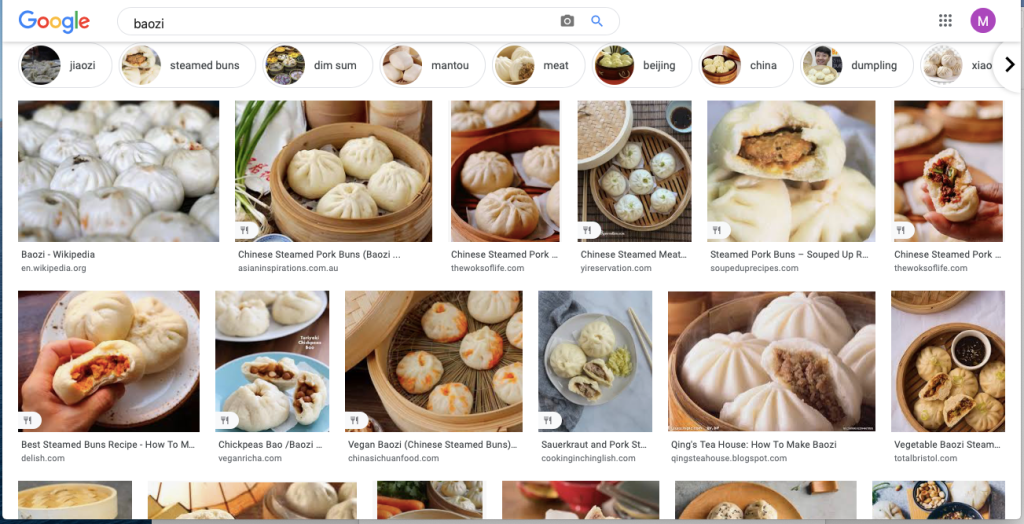

In recent years, the light and fluffy Chinese delicacy that is the baozi, or bao, has found its way into restaurants and kitchens across the globe. Their being steamed, combined with the yeast within the dough, makes for a soft and delicately spongey texture, quite unlike any other kind of baked bread or steamed dumpling.

Our lexical disclaimer for today is here to inform you that ‘bao’ in itself translates as ‘bun’ in Mandarin, and so the commonly-used Western phrase ‘bao bun’ is grammatically redundant, literally meaning ‘bun bun’, in the same way that in Hindi, ‘Chai tea’, actually means ‘tea tea’.

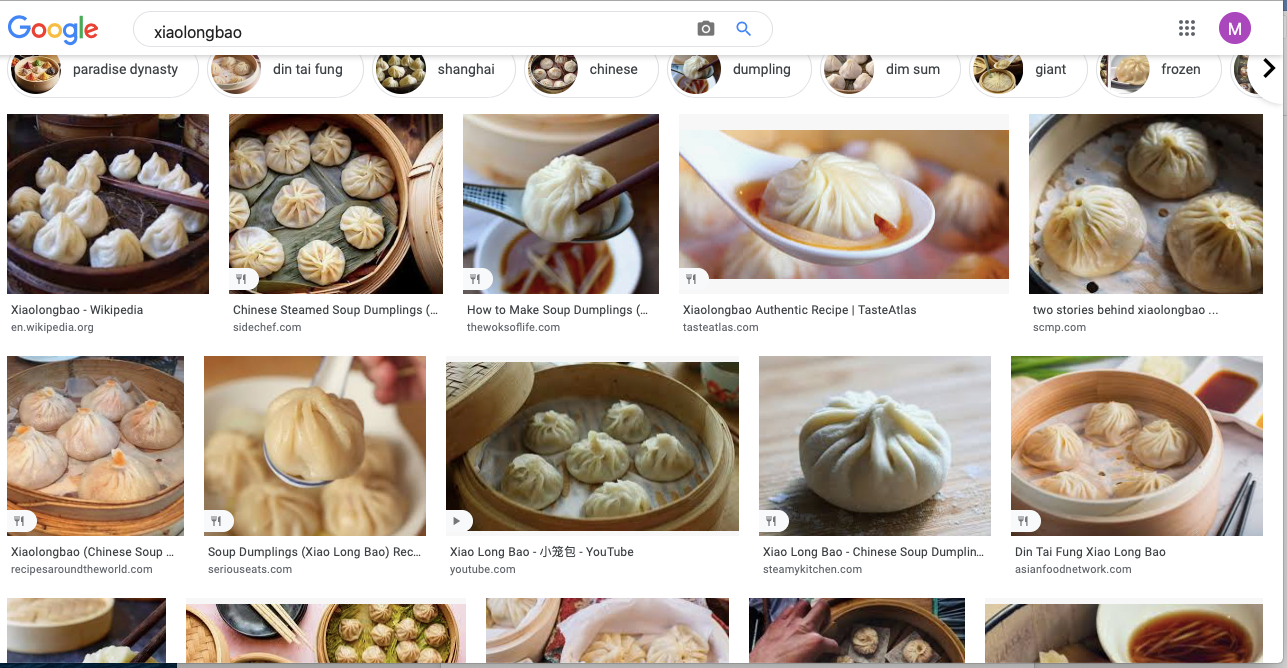

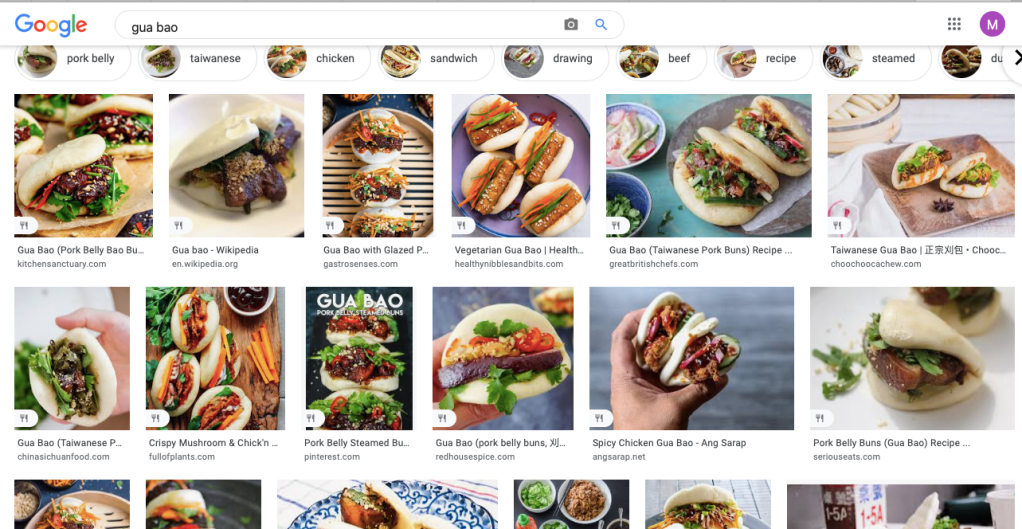

Generally baozi are a filled ‘bun’, with the dough gathered together on top, sometimes leaving a small hole for steam to escape, and complete with either a meat or vegetable filling. One of the most popular is the Char Siu Bao, filled with sticky barbecued pork. Other variants include the xiaolongbao, with xiaolong referring to the bamboo steaming basket in which they are cooked and served., This bao is filled with a hot soup, and is sometimes referred to as a dumpling. The final type of bao that I’ll touch on is the gua bao, which comprises of a flat, open steamed lotus-leaf bun, with a meat (often pork belly) filling.

As ever with Chinese food, it’s very difficult to generalise, as regional cuisines across what is such a huge country vary so significantly. Whether we’re talking baozi, xiaolongbao or gua bao, these may be more prevalent in certain provinces, or be made differently in others, and so defining such a specific part of incredibly complex and diverse cuisine is pretty tricky to do in a few hundred words!

…….

Career changes, and COVID combined meant that my dreams of heading to China this year were scuppered, and so I’ve never tried these dreamy little buns in their homeland. Living in London does mean however, that there are a million one street food stalls, Chinatown restaurants, and chains that serve up these little beauties, although of course I’m unable to comment on their authenticity.

Interestingly, many of the places in which I tried bao/baozi weren’t actually Chinese-influenced, and include Malay, Vietnamese and Japanese-inspired food businesses to name a few. The very first time I tried baozi was years ago at a little independent restaurant back in Nottingham, called Yumacha, which describes itself as serving up ‘an eclectic mix of the Far East’s favourite dishes’. These kind of ‘Asian fusion’ restaurants seem to be on the rise, combining Chinese, Japanese, Thai and Indonesian cuisine plus a whole lot more. I had no idea what I was eating at the time, with the concept of a steamed bun seeming completely alien to me – I have to say this was many years before my foodie instinct really kicked in, and my knowledge of the food I was eating was minimal. Despite this, I loved the unfamiliar, cloud-like texture of the buns, along with their punchy flavoured meat fillings.

Fast-forward a good 5+ years, and I’ve tried a fair few variations. Popular Vietnamese Keu Deli in London serves up a giant baozi, which definitely wins points for the lightest, most satisfying bao texture. BaoziInn in Chinatown is a solid bet for quality baozi, which were slightly flatter in my experience, and fillings include the pork-patty-like stuffing that I tried.

Admittedly, I’ve yet to try xiaolongbao, possibly because I’ve distanced them from the baozi that I love, as they do tend to resemble dumplings, and the hot broth filling has never appealed to me as much as a juicy meaty filling.

Gua bao , however, might be my favourite, based on those that I’ve tried. They have the most wonderfully smooth texture, and oddly, more filling seems to be packed into these open bao than stuffed within the closed, larger baozi.

My favourites so far were from Thai-Malaysian street food stall Satay Street ,where I was lucky enough to win a competition for two free portions. I tried a curried chicken bao and a satay chicken bao, both of which were great, with the satay flavour being particularly delicious.

I have to admit that the first gua bao I ever tried was actually from Wagamama – I think they’d just added it to the menu, as they were giving away samples outside with a pulled beef style filling, and it was pretty good. There’s only been one occasion where I’ve not been able to finish a gua bao, and I won’t name the business, but it was the filling rather than the bun that I couldn’t stomach – I can only hope you never stumble across it yourselves!

DIY BAO

Baking your own bao at home seems like such a daunting exercise, and I have had varying degrees of success. The first time I tried it was a BBC GoodFood recipe, with a pork belly filling, and whilst the filling with sticky and sweet, as you can see, my buns failed entirely, ending up flat as pancake, stodgy and generally quite grim. Whether this was the recipe, my techniques, or dodgy ingredients I couldn’t tell you, but it didn’t bode well for future attempts.

That’s why I was so surprised when I tried Queen Nadiya’s recipe for spicy tuna bao, and they turned out excellently. From her ‘Time to Eat’ cookbook, this is a recipe I would 100% recommend – there’s definitely a little effort required, but with such impressive results, it’s worth it. The buns are super filling but the tuna itself is light, fresh-tasting, and umami, and when a recipe like this goes to plan, there’s a real sense of achievement waiting for you on the other side.

I’m sure there are a huge number of people who still have never tried any form of bao, and if you’re one of them I really urge you to do so. I can’t think of a single other food that compares in texture to these perfect little buns, and with fillings being so varied, there’s bound to be something to suit all tastes.

¡Comemos!

xo