It’s been a while since our last virtual food adventure, but I’m back at it, and this time we’re heading to Lebanon, for a baked breakfast treat that’ll make you question why eating flatbreads for breakfast isn’t the norm here…

I have tried desperately hard throughout this piece to use the singular form of today’s featured dish as the plural version completely changes the word and I can’t bear to incompetently destroy the language… so without further ado, welcome the Man’ousheh.

Origins…

Similar to what we learnt from the Hungarian Lángos, the Man’ousheh (there are also spelling variations) traditionally came from the haul of bread that women would bake in the mornings to feed their families. Smaller portions of dough would go towards making the Man’ousheh for breakfast.

Bread historically has played such a huge part in many cuisines across the globe, being a staple way to feed a family, and one that has unique features in various countries. Compare the fried or baked Lángos commonly topped with sour cream and cheese with the thinner Man’ousheh, heavily spiced with za’atar, sesame seeds and minced lamb to name a few common toppings. You could go from a Turkish stuffed gozlëme flatbread to Spanish pan con tomate, but regardless of where you are, variations of bread-based dishes have been feeding us for centuries.

Terminology…

As I begin to think more deeply about cultural appropriation and the exoticisation of food, I’d like to add a disclaimer here about the use of the word ‘flatbread’. There’s sometimes debate when it comes to equating one country’s produce to that of another nation, for example, lots of articles talk of the Man’ousheh as the Lebanese ‘pizza’. A man’ousheh really isn’t a non-Italian pizza, and actually, only an Italian pizza is an Italian pizza… Therefore trying to equate the two risks ignorance. I’ve also seen some posts questioning the depiction of the Man’ousheh as a flatbread. At the end of the day, a Man’ousheh is simply a Man’ousheh, however, when language and cultural barriers prevent us from understanding what that actually consists of, it can be useful to make comparisons.

The difference between referring to it as a flatbread and as a pizza, is that flatbread is a much more generic term that doesn’t refer to one specific dish from a specific culture, and instead types of flatbread can be found globally. On the other hand, the term ‘pizza’ has more limitations, and almost suggests the idea that the Man’ousheh is trying to live up to a European classic, but hasn’t quite hit the mark.

It’s these kinds of connotations that we should be aware of when comparing food from different backgrounds – let’s eliminate the unquestioned assumption that everything we’re not familiar with is a variation of something we already know. Instead, we should appreciate that there’s a wealth of food out there that goes beyond our personal experience.

With our less-than-inspiring culinary reputation here in the UK, we, more than anyone, should be aware that actually there’s very little we did invent on the food front, and so much that we’ve adopted here stems from the influence of other cultures. The terminology we use should respect and appreciate the food we’re discussing, only using generic comparisons when essential for explanatory purposes.

From Lebanon to London

Lengthy disclaimer aside, nowadays the Man’ousheh can be found in bakeries across the Levant, and has even branched out further afield, gaining attention in the US and here in London. The Lebanese Bakery is one of the best places in the city to try a Man’ousheh, and it actually has stores in Beirut too, which should tell you exactly how legit it is. Their menu’s full of Middle Eastern flavours and toppings, including halloumi, pine nuts, pomegranate molasses and various yoghurts. They even do sweet versions topped with Nutella, tahini and honey.

As well as a basic flatbread with hummus, I ordered their all-day breakfast Man’ousheh with baked eggs and awarma (lamb confit). It looked beautiful, with its plaited crust and dazzling egg yolks, and for £6.95, they’re very reasonably priced.

Home cooking

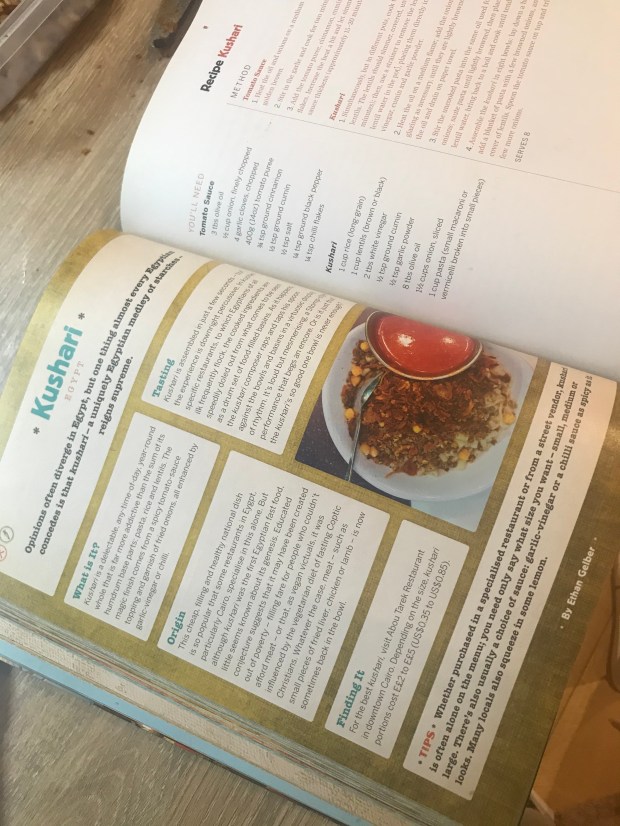

Moving from the experts to my home kitchen, things aren’t as pretty. I love my Lonely Planet Street Food cookbook for its array of recipes for much-loved snacks and on-the-go dishes across the world, so I thought I’d give baking a Man’ousheh a go myself.

As you can see, definitely not as attractive as those made by the professionals, which is to be expected, but it was ok. The dough definitely wasn’t as light and fluffy, and instead was much thinner with more of a crunch to it, however, it was edible, and sometimes that’s all I’m asking for. I avoided the temptation to shovel as much meat and cheese on top as I could manage, and instead opted for a lighter za’atar, sesame seed and date topping.

If you’re inspired to have a go at home, although the Lonely Planet recipe worked, I’m 100% sure there are much better recipes out there, so it’s really not tricky at all, but just give it a Google and take your pick.

Failing that, trying a Man’ousheh at The Lebanese Bakery is highly recommended for a substantial shared snack or a solid lunch (or very solid breakfast…).

I have no idea where I’m going next time so off I go to get planning for the next edition of Around the World in 80 Plates!

¡Comemos!

xo